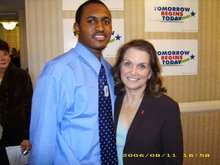

U.S. Rep. Artur Davis is eyeing the governor's suite in a Capitol where Jefferson Davis took the oath as president of the Confederacy, where Gov. George Wallace declared "Segregation forever!" 45 years ago in his first inaugural address.

Artur Davis wasn't even born when that happened. He grew up in an Alabama with integrated schools and with blacks filling one-fourth of the seats in the Legislature.

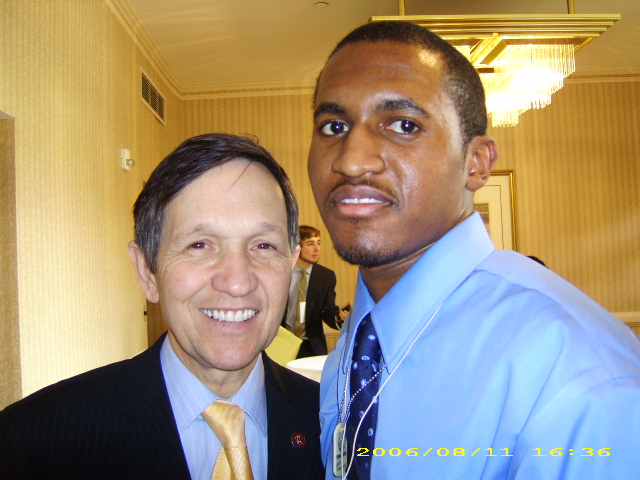

As the nation weighs whether to elect a black president in November, the prospect of a Davis candidacy for governor of Alabama in 2010 quietly grows. The 40-year-old's proven abilities to raise funds and woo white voters - knacks that are not unlike Obama's - have convinced some that the question isn't whether he has the tools to win a statewide campaign.

It's whether the state is ready for him.

"He is a unifier, but is he enough of a unifier to overcome the history of Alabama?" asked D'Linell Finley, a black political scientist at Auburn University Montgomery.

Davis, a moderate Democrat, is reaching out to potential donors and making speeches far outside his majority black 7th District, which curves southwest from Birmingham through some of the nation's poorest counties in west Alabama and ends just past Selma, a proving ground in the voting-rights movement.

He's built up nearly $1 million in his congressional campaign account that he could spend on a bid for governor.

Yet he is a realist: "Nobody like me has ever been governor of Alabama. But I was inspired by other people who didn't let that stop them," he said recently.

Davis cites former Gov. Douglas Wilder in Virginia and two-time gubernatorial candidate Tom Bradley in California, both black. But only two black candidates have been elected to statewide office in Alabama in modern times.

In 2002, Davis defeated Earl Hilliard, Alabama's first black congressman since Reconstruction by attracting Jewish voters upset by the incumbent's visit to Libya and his vote against a pro-Israel resolution. Davis then delivered the same message at predominantly white civic clubs and chamber of commerce meetings as he did at black churches.

"We've had very strong support across racial lines in my district. Frankly, that, from a political standpoint, is the thing I'm proudest of," he said.

Merle Black, a political scientist at Emory University in Atlanta, said Georgia has elected an African-American attorney general and labor commissioner because they ran as centrists, just like Wilder.

"If Artur Davis is going to have a chance to win a statewide race, he's going to have to have biracial appeal and not just be a spokesman for black advancement," said Ferrell Guillory, director of the University of North Carolina's Program on Southern Politics, Media, and Public Life. "He's got to run like Barack Obama, not Jesse Jackson."

Davis describes himself as more conservative than his friend Obama. When he talks about issues, he doesn't appeal to people's altruism. He makes a practical argument he calls "enlightened self-interest."

At the stately Vestavia Hills Country Club, literally and figuratively over the mountain from Davis' district in neighboring Birmingham, he recently told a mostly white audience of business people that they need to care about more than just their local schools. He told them that if their mothers have to be admitted to the hospital in Birmingham, the orderlies changing the sheets, the cooks fixing the meals and the technicians drawing the blood will likely be products of Birmingham's inner-city schools.

"If you want them to know what they are doing, you have just discovered your linkage to the Birmingham city schools," he said.

People lined up for more than 20 minutes to talk to him afterward, even though they don't vote in his district.

Davis agreed to be Obama's Alabama chairman shortly after the Illinois senator entered the race, when Hillary Rodham Clinton had a strong lead in the polls in Alabama and the support of some of the state's top black politicians.

When the predominantly black Alabama New South Coalition met to make an endorsement in December, Davis got to the meeting early and personally lobbied each member. The group surprised itself by voting to endorse Obama rather than making a joint endorsement.

Like Obama, Davis' parents divorced when he was young. His father, a nurse, moved to California. His mother, a teacher, and his grandmother raised him in a small home next to railroad tracks on Montgomery's west side.

"I was painfully shy as a child growing up," he recalled, hitting on one big difference between himself and Obama.

Davis spent many days in the public library reading books rather than hanging out with friends. He still grimaces when he talks about those days.

"I had a giant Afro way past the point where they were fashionable. I had glasses, which are fine when you are older, but they are not so great when you are 16 and 17," he said.

Those hours in the library were Davis' ticket to Harvard, where his shyness continued. It was not until he got hired as an assistant U.S. attorney in Montgomery that he began to feel comfortable in front of an audience.

"Being a lawyer and standing up and arguing in front of juries, that was probably the best political training I got," he said.

A measure of Davis' appeal is found in Hueytown, best known as the hometown of former NASCAR stars Bobby and Donnie Allison. In a predominantly white, working-class precinct in 2004, Democratic presidential nominee John Kerry got 23 percent of the vote. Further down the ballot, Davis got 77 percent.

"That happened because they saw me as someone who represented their interests and didn't see their interests as divergent from the African-Americans who lived behind the corner from them or lived in the rest of the district," said Davis.

On Thursday in Mobile, well outside Davis' district, welder and registered voter Warren Kelly said he had not heard of Davis, but that in "this day and age" race would not be a factor in a Davis candidacy.

"There's a black man running for president," said Kelly.

Joe Bearrentine, a construction subcontractor from Montgomery who's white, said Thursday that if Davis ran for governor, race would not be a factor - at least not for him.

"I could vote for a black person as easily as a white person," Bearrentine said. "But I don't think most people feel that way."

Associated Press writer Garry Mitchell in Mobile contributed to this report.

No comments:

Post a Comment