Short Freddie Mac stay made him at least $320,000Before its portfolio of bad loans helped trigger the current housing crisis, mortgage giant

Freddie Mac was the focus of a major accounting scandal that led to a management shake-up, huge fines and scalding condemnation of passive directors by a top federal regulator.

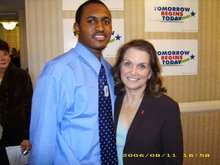

One of those allegedly asleep-at-the-switch board members was Chicago's

Rahm Emanuel—now chief of staff to

President Barack Obama—who made at least $320,000 for a 14-month stint at Freddie Mac that required little effort.

As gatekeeper to Obama, Emanuel now plays a critical role in addressing the nation's mortgage woes and fulfilling the administration's pledge to impose responsibility on the financial world.

Emanuel's Freddie Mac involvement has been a prominent point on his political résumé, and his healthy payday from the firm has been no secret either. What is less known, however, is how little he apparently did for his money and how he benefited from the kind of cozy ties between Washington and Wall Street that have fueled the nation's current economic mess.

Though just 49, Emanuel is a veteran Democratic strategist and fundraiser who served three terms in

the U.S. House after helping elect

Mayor Richard Daley and former

President Bill Clinton. The Freddie Mac money was a small piece of the $16 million he made in a three-year interlude as an investment banker a decade ago.

In business as in politics, Emanuel has cultivated an aggressive, take-charge reputation that made him rich and propelled his rise to the front of the national stage. But buried deep in corporate and government documents on the Freddie Mac scandal is a little-known and very different story involving Emanuel.

He was named to the Freddie Mac board in February 2000 by Clinton, whom Emanuel had served as

White House political director and vocal defender during the Whitewater and Monica Lewinsky scandals.

The board met no more than six times a year. Unlike most fellow directors, Emanuel was not assigned to any of the board's working committees, according to company proxy statements. Immediately upon joining the board, Emanuel and other new directors qualified for $380,000 in stock and options plus a $20,000 annual fee, records indicate.

On Emanuel's watch, the board was told by executives of a plan to use accounting tricks to mislead shareholders about outsize profits the government-chartered firm was then reaping from risky investments. The goal was to push earnings onto the books in future years, ensuring that Freddie Mac would appear profitable on paper for years to come and helping maximize annual bonuses for company brass.

The accounting scandal wasn't the only one that brewed during Emanuel's tenure.

During his brief time on the board, the company hatched a plan to enhance its political muscle. That scheme, also reviewed by the board, led to a record $3.8 million fine from the Federal Election Commission for illegally using corporate resources to host fundraisers for politicians. Emanuel was the beneficiary of one of those parties after he left the board and ran in 2002 for a seat in Congress from the North Side of Chicago.

The board was throttled for its acquiescence to the accounting manipulation in a 2003 report by Armando Falcon Jr., head of a federal oversight agency for Freddie Mac. The scandal forced Freddie Mac to restate $5 billion in earnings and pay $585 million in fines and legal settlements. It also foreshadowed even harder times at the firm.

Many of those same risky investment practices tied to the accounting scandal eventually brought the firm to the brink of insolvency and led to its seizure last year by the Bush administration, which pledged to inject up to $100 billion in new capital to keep the firm afloat. The Obama administration has doubled that commitment.

Freddie Mac reported recently that it lost $50 billion in 2008. It so far has tapped $14 billion of the government's guarantee and said it soon will need an additional $30 billion to keep operating.

Like its larger government-chartered cousin

Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac was created by Congress to promote home ownership, though both are private corporations with shares traded on the

New York Stock Exchange. The two firms hold stakes in half the nation's residential mortgages.

Because of Freddie Mac's federal charter, the board in Emanuel's day was a hybrid of directors elected by shareholders and those appointed by the president.

In his final year in office, Clinton tapped three close pals: Emanuel, Washington lobbyist and golfing partner James Free, and Harold Ickes, a former White House aide instrumental in securing

the election of

Hillary Clinton to the U.S. Senate. Free's appointment was good for four months, and Ickes' only three months.

Falcon, director of the Office of Federal Housing Enterprise Oversight, found that presidential appointees played no "meaningful role" in overseeing the company and recommended that their positions be eliminated.

John Coffee, a law professor and expert on corporate governance at

Columbia University, said the financial crisis at Freddie Mac was years in the making and fueled by chronically weak oversight by the firm's directors. The presence of presidential appointees on the board didn't help, he added.

"You know there was a patronage system and these people were only going to serve a short time," Coffee said. "That's why [they] get the stock upfront."

Financial disclosure statements that are required of U.S. House members show Emanuel made at least $320,000 from his time at Freddie Mac. Two years after leaving the firm, Emanuel reported an additional sale of Freddie Mac stock worth between $100,001 and $250,000. The document did not detail whether he profited from the sale.

Sarah Feinberg, a spokeswoman for Emanuel, said there was no conflict between his stint at Freddie Mac and Obama's vow to restore confidence in financial institutions and the executives who run them. At the same time, Feinberg said Emanuel now agrees that presidential appointees to the Freddie Mac board "are unnecessary and don't have long enough terms to make a difference."

Former

President George W. Bush voluntarily stopped making such appointments following Falcon's assessment of their uselessness.

In an interview, Falcon said the Freddie Mac board did most of its work in committees. Yet proxy statements that detailed committee assignments showed none for Emanuel, Free or Ickes during the time they served in 2000 or 2001. Most other directors carried two committee assignments each.

Contrary to the proxy statements, Feinberg said she believed that Emanuel served on board committees that oversaw Freddie Mac's investment strategies and mortgage purchase activities. But Feinberg acknowledged she had no official documents to back up that assertion.

The Obama administration rejected a Tribune request under the Freedom of Information Act to review Freddie Mac board minutes and correspondence during Emanuel's time as a director. The documents, obtained by Falcon for his investigation, were "commercial information" exempt from disclosure, according to a lawyer for the Federal Housing Finance Agency.

Emanuel's board term expired in May 2001, and soon after he launched his Democratic congressional bid.

One of Emanuel's fellow directors at Freddie Mac was Neil Hartigan, the former Illinois attorney general. Hartigan said Emanuel's primary contribution was explaining to others on the board how to play the levers of power.

He was respected on the board for his understanding of "the dynamics of the legislative process and the executive branch at senior levels," Hartigan recalled. "I wouldn't say he was outspoken. What he was, was solid."

By the time Emanuel joined Freddie Mac, the company had begun to loosen lending standards and buy riskier sub-prime loans. It was a practice that later blew up and contributed to the current foreclosure crisis.

In his investigation, Falcon concluded that the board of directors on which Emanuel sat was so pliant that Freddie Mac's managers easily were able to massage company ledgers. They manipulated bookkeeping to smooth out volatility, perpetuating Freddie Mac's industry reputation as "Steady Freddie," a reliable producer of earnings growth. Wall Street liked what it saw, Freddie Mac's stock value soared and top executives collected their bonuses.

Another focus of Freddie during Emanuel's day—and one that played to his skill set—was a stepped-up effort to combat congressional demands for more regulation.

During a September 2000 board meeting—midway through Emanuel's 14-month term—Freddie Mac lobbyist R. Mitchell Delk laid out a strategy titled "Political Risk Management" aimed at influencing lawmakers and blunting pressure in Congress for more regulation. Through Delk's initiative, Freddie Mac sponsored more than 80 fundraisers that raised at least $1.7 million for congressional candidates despite a federal law that bans corporations from direct political activity.

Emanuel spokeswoman Sarah Feinberg said Emanuel "can't remember the meeting or topic" but might have been in attendance when Delk outlined his plans. Feinberg downplayed the significance of the fundraiser thrown for Emanuel, which brought in $7,000, stressing that it was but one of many hosted by Delk. The event stood out in at least one respect, however.

The Freddie Mac-linked events were mostly for

Republicans, and only a handful benefited

Democrats like Emanuel. "Rahm was a good friend of mine. He was on Freddie Mac's board. He was very much supportive of housing," said Delk, who resigned under pressure in 2004.

Then-Freddie Mac CEO Leland Brendsel also hosted a fundraising lunch for Emanuel's 2002 campaign that netted $9,500 from top company executives. Brendsel was later ousted in the accounting scandal.

Federal campaign records show that Emanuel received $25,000 from donors with ties to Freddie Mac in the 2002 campaign cycle, more than twice the amount collected that election by any other candidate for the U.S. House or Senate.

Emanuel joined the House in January 2003 and was named to the Financial Services Committee, where he also sat on the subcommittee that directly oversaw Freddie Mac. A few months later, Freddie Mac Chief Executive Officer Leland Brendsel was forced out, and the committee and subcommittee launched hearings to sort out the mess, spanning more than a year. Emanuel skipped every hearing, congressional records indicate.

Feinberg said Emanuel recused himself "from deliberations related to Freddie Mac to avoid even the appearance of favoritism, impropriety or a conflict of interest."

bsecter@tribune.comazajac@tribune.com